Guidance

This guidance provides practical help on what a proportionate and integrated approach to risk management might look like and how trustees could go about putting one in place. It should be read in conjunction with the DB funding code.

Issued: December 2015

About this guidance

What is the purpose of this document?

The code of practice on funding defined benefits (the ’DB funding code’) provides a principles-based framework on how to comply with the statutory funding requirements contained in Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004 (’Part 3’).

Integrated Risk Management (IRM) is an important tool for managing the risks associated with scheme funding. It forms an important part of good governance. The defined benefit (DB) funding code sets out the importance of trustees adopting an integrated approach to risk management. It also provides a basic framework for doing so[1].

This IRM guidance provides practical help on what a proportionate and integrated approach to risk management might look like and how trustees could go about putting one in place. It should be read in conjunction with the DB funding code.

Who should use this guidance?

This guidance should be used by the trustees and employers of trust-based DB occupational pension schemes required to comply with the statutory funding requirements in Part 3. It will also be of use to their advisers.

How should this guidance be used?

While it is aimed at all employers and trustees, we believe that trustees of smaller schemes may find it of particular help.

Some of the text in this guidance is highlighted in purple boxes to emphasise key principles and questions for consideration.

Examples are used to illustrate concepts and provide practical guidance. Not all examples will be relevant to every scheme – the extent to which these are informative will depend on the scheme’s and the employer’s circumstances.

The terms used in this document should be read consistently with those in Part 3 and in the DB funding code.

The appendix to this guidance is technical in nature. Before studying ts content, we recommend that readers become familiar with the main guidance.

What other guidance could be useful?

- The DB funding code.

- Code of practice module on internal controls.

- Assessing and monitoring the employer covenant (’covenant guidance’) – which provides guidance to trustees on how to assess, monitor and take action to improve the employer covenant of a DB scheme.

- Guidance on DB scheme investment strategy.

Footnotes for this section

- [1] See paragraphs 38 to 60 of the DB funding code.

Terms used in this guidance

Contingency plans: Plans setting out actions that will be undertaken in certain circumstances to limit the impact of risks that materialise or to introduce additional risk capacity. ’Contingency planning’ should be construed accordingly.

Funding risk: The risk that the actuarial and other assumptions used to calculate the scheme’s technical provisions and any recovery plan (or any other target the trustees and employer have agreed to track) are incorrect and liabilities exceed assets in future by a greater margin than anticipated.

IRM approach: The practical steps and decisions taken by the trustees to introduce, maintain and develop IRM for their scheme as represented by the process diagram under paragraph 12.

IRM framework: The output of the trustees’ and employer’s IRM approach in terms of its agreed processes, procedures and documentation to be used by current and future trustees, for and between subsequent valuations.

Overall strategy: The sum of the various strategies the trustees have in place in order to meet their scheme objective. These strategies will include, but are not limited to, decisions taken regarding the Part 3 technical provisions assumptions and recovery plan (and any other secondary funding target or plan the trustees may agree with the employer) and the trustees’ investment strategy.

Part 3: Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004.

Risk appetite: The trustees’ or employer’s readiness to accept a given level of risk.

Risk capacity: The scheme’s or employer’s ability to absorb or support risks.

Scheme objective: This covers the trustees’ objective to pay benefits promised in accordance with their scheme rules as and when they fall due linked to the statutory funding objective, and to have sufficient and appropriate assets to cover their scheme’s technical provisions under Part 3[2].

Footnotes for this section

- [2] See section 222 of the Pensions Act 2004.

What is IRM?

1. IRM is a risk management tool that helps trustees identify and manage the factors that affect the prospects of meeting the scheme objective, especially those factors that affect risks in more than one area. The overall strategy the trustees have in place to achieve this objective will be dependent on the scheme’s and employer’s circumstances from time to time.

2. The output of an IRM approach informs trustee and employer discussions and decisions in relation to their overall strategy for the scheme. This encompasses risk capacity, risk appetite and contingency planning as well as the assumptions to be used for calculating the scheme’s technical provisions and any recovery plan. If a scheme has a secondary funding target (as well as the statutory funding objective) or journey plans, then IRM also helps to manage the scheme against this secondary target or plan.

3. IRM is a method that brings together the identified risks the scheme and the employer face to see what relationships there are between them. It helps prioritise them and to assess their materiality. It can take many forms but should involve an examination of the interaction between the risks and a consideration of 'what if' scenarios to test the scheme's and employer's risk capacities. Quantification of risks may help these considerations but the rigour of quantification should be proportionate to the risk and resources available.

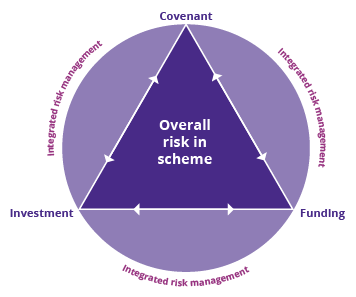

4. If the three fundamental risks to DB schemes are illustrated as a triangle with employer covenant, investment and funding risks at each corner, and each edge of the triangle examines the relationship between two risks bilaterally (for example, the right edge examines the relationship between covenant and scheme funding), IRM is the surrounding circle that encompasses all these risks together. IRM investigates the relationships between these risks (the triangle edges) altogether, examines their interrelationship and seeks to understand how risk at one corner of the triangle might affect the other two.

5. The DB funding code and our separate covenant and investment guidance provide more material on the three DB scheme risks at the triangle corners. Ultimately the employer covenant underwrites investment risks and funding risk held within the scheme. If too much risk exists under the scheme relative to the employer covenant, it is more likely that the scheme objective will not be met.

6. IRM goes further than merely understanding risks. It also considers what could be done should risks materialise (especially those which impact across more than one area). It may be necessary for contingency plans to be put in place to cater for the more significant risks. In addition, IRM helps to identify when opportunities arise to reduce scheme risk.

7. IRM also informs the trustees' approach to monitoring these risks, implementing their contingency plans and, where necessary, adapting those plans as events unfold.

8. Most schemes should be able to apply most of the key steps for IRM. Its sophistication can be scaled up or down depending on the scheme and employer’s circumstances and needs, allowing for it to be proportionate.

9. Implementing effective IRM requires good governance. Trustees need to establish appropriate internal governance (for example, using sub-committees) and ensure their advisers are working together to deliver advice in the form trustees need to take their decisions.

10. IRM is not a replacement process for identifying what the scheme’s overall strategy should be. However, where the strategy has to change, an IRM approach will inform the change by identifying any additional risk associated with it.

Key principles/questions for consideration

The key benefits of IRM are:

Risk identification: the ability to identify, prioritise and ideally, where proportionate, quantify the material risks to the scheme objective. It also provides an assessment of the interrelationships between these material risks.

Better decision making: greater trustee and employer understanding of the material risks (including their chance of occurring and interrelationships) to the scheme objective allowing for better informed decision making.

Collaboration: open and constructive dialogue between trustees and employers about the material risks to each other’s strategies (useful as a starting point for future engagement enabling quantification of the employer’s and scheme’s risk capacities and identification of a risk appetite for both the trustees and employer).

Proportionality: a focus on the most important risks helping trustees to adopt a proportionate approach to risk assessment, contingency planning and monitoring of material risks – IRM does not necessarily mean spending more time and money on scheme governance (it might require greater effort to initiate but should result in time and cost savings subsequently).

Efficiency: effective management of trustees’, employer’s and advisers’ time.

Risk management: having plans in place to monitor and manage the material scheme risks allows swifter reactions to events should problems arise.

Transparency: easier explanation of decisions to third parties, including us, especially when the process for risk assessment and management has been documented.

Key principles/questions for consideration

Essentially IRM answers these questions:

For the trustees and employer together:

- What are the scheme risks to the overall strategy for meeting their scheme objective?

- What are the probabilities of these risks materialising?

- What are the relationships between the risks?

- What are the capacities of the scheme and employer to put scheme funding and/or the employer position back on track should the risks materialise? What steps would that involve taking?

- What are their risk appetites?

- If the risks are greater than their risk appetites, should the overall strategy for meeting the scheme objective be changed?

- What monitoring should be put in place for scheme funding and/or the employer position?

- What options are available should scheme funding and/or the employer position improve?

For the trustees

- What is the potential impact for both the scheme and employer of the risks they are taking (or proposing to take) in their funding plans?

- Having discussed with the employer the resources it has available, are the trustees comfortable that the scheme and the employer have sufficient risk capacities to manage that impact?

For the employer

- Is it aware of the impact managing the risk could have on its finances (both in the short and longer term)?

- Is it able to manage the potential impact of the current (or proposed) scheme risk?

- How well does it understand the options available to manage those risks and the costs and benefits of those different options?

What does IRM look like in practice?

Key principles/questions for consideration

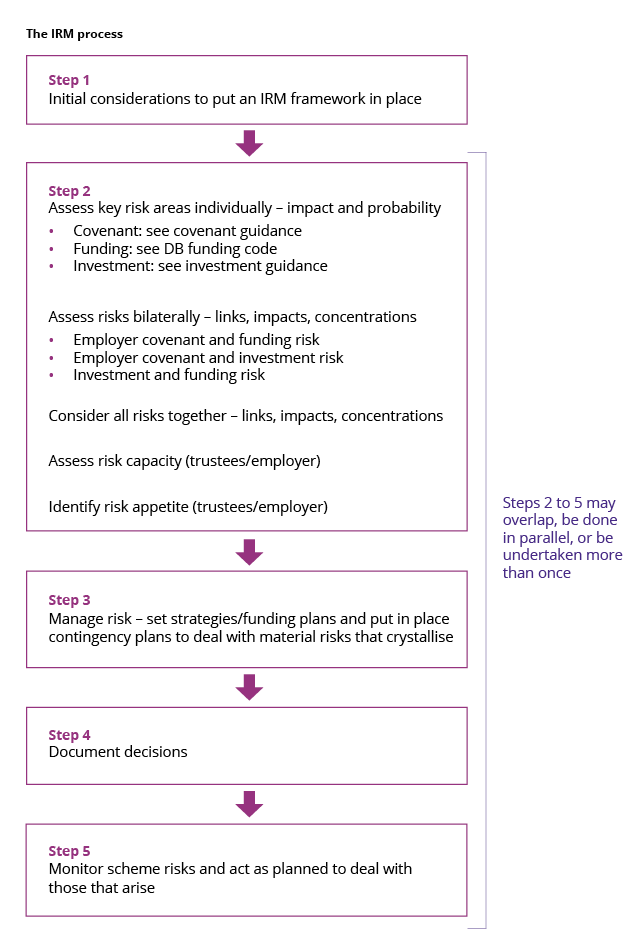

There are five important steps associated with effective IRM:

Step 1: Initial considerations for putting an IRM framework in place

Step 2: Risk identification and the initial risk assessment

Step 3: Risk management and contingency planning

Step 4: Documenting the decisions

Step 5: Risk monitoring

11. When these steps have been completed, the trustees will have an IRM framework that sets out both their and the employer’s approach to IRM.

12. The following diagram outlines a logical process for these steps to implement IRM. Steps 2 to 5 are iterative. They may overlap, be done in parallel, or be undertaken more than once.

Step 1: Initial considerations for putting an IRM framework in place

13. There is no one set formula for what IRM should look like. It will be determined by, and will be proportionate to, the trustees’ scheme objective and the employer’s objectives, in the light of their needs and circumstances.

14. Trustees should consider introducing IRM wherever the scheme lies within its actuarial valuation cycle. It does not have to wait until the next valuation is due.

15. Putting an IRM framework in place, with appropriate documentation, requires an initial investment of time and resources. This will then be repaid as the framework is used by current and future trustees, for and between subsequent valuations.

16. The extent of that initial investment will vary between schemes. Many schemes already have a risk assessment and management process in place. It may not be labelled as IRM but its steps and outputs may be similar. Schemes without such a process already should, nonetheless, find that the basic IRM inputs are in hand (for example, covenant assessment, actuarial and investment reports).

17. Trustees are responsible for ensuring that their scheme’s IRM approach is appropriate and effective. They should consider who should be involved in the process, how they will engage with the employer and how advisers should work together.

18. IRM works best when the trustees and employer work together. Their interests are often aligned such as with their mutual interest in sustainable growth of the employer. IRM helps the trustees and employer to understand each other’s risk capacities and appetites. Additionally this engagement may assist the employer in relation to any company financial reporting requirements.

19. In multi-employer schemes, it is beneficial for the IRM framework if the employers have an agreed risk capacity and risk appetite. This is likely where the employers are all part of the same group. In such schemes, the principal employer or another nominated employer generally engages with the trustees on behalf of all of them. The nominated employer should similarly engage with the trustees to communicate the employers’ agreed risk capacity and appetite when agreeing an IRM framework.

20. In non-associated multi-employer (NAME) schemes, the employers might not initially have an agreed risk capacity and risk appetite. This is because there will be employers of different sizes and their businesses may be focused on different industry sectors. In addition, some employers within NAME schemes may be commercial competitors. It would be best practice and more efficient for the employers to nominate representatives to agree a collective risk capacity and risk appetite. Having a collective employer risk capacity and risk appetite will enable the IRM framework to operate more smoothly. The nominated representatives should then engage with the trustees to put in place an IRM framework on behalf of all the employers.

21. Sometimes the trustees and employer may have different views on their risk capacities and risk appetites, and/or what risk management actions to take. However, each party should understand both the reasons for the other’s views and the consequences of choosing a different risk capacity or risk appetite. This is partly because the risks faced by the parties are interdependent and partly because understanding the other’s views and their rationale makes it more likely that a funding agreement can be reached.

Example 1: Working with the employer

The employer co-operated with the trustees on scheme funding but was not prepared to commit additional resources to work with the trustees as they developed an IRM approach. Instead, the employer tended to react to the scheme’s circumstances as they emerged rather than plan in advance to address risks. The trustees worked hard to be transparent over the level of risk the scheme posed, especially those that flowed from the scheme’s investment strategy. These were within the employer’s risk capacity – the trustees had taken advice to confirm that the covenant was sufficient – but, other than covenant, there were no steps in place, such as contingency plans, to manage the risk of investment underperformance. The employer had encouraged the trustees to adopt the relatively risky investment strategy because it was expected to keep the contributions down. However, market conditions produced investment underperformance and in the absence of any other options there was a need to increase contributions. Even though the employer could bear the increased contributions, they disrupted its business plans.

Guidance: A thorough approach to IRM has benefits even when the trustees are satisfied that the scheme’s risks are within the employer’s risk capacity. Furthermore, an initial investment in IRM by both trustees and employer can lead to greater collective understanding, as well as better focused and more cost-effective advice and decision making.

In this case, failure to take advantage of an IRM approach and make advance plans meant that the business continued to be reactive to risk. As a result, it missed the opportunity to put in place a framework that would have allowed it to support the scheme and progress its business plans without disruption.

22. Trustees might wish to ask one (or a small number) of their advisers who have more experience in this area to take the lead in putting the IRM framework in place initially. While all trustees remain responsible for scheme governance, they are likely to find it helpful to give oversight responsibility to a committee once the framework is established, to ensure that advice from different sources is drawn together and co-ordinated efficiently. This includes ensuring that advisers work together effectively, and that relevant trustee subcommittees work in a connected manner, for example by holding joint meetings where needed. Given the importance of IRM, it is important for the committee with oversight responsibility to report directly to the main trustee board.

Example 2: IRM governance

The trustees decide that their investment adviser is the best person to initially co-ordinate putting in place and implementing their IRM approach. This is due to the trustees’ inexperience in this field. They want to learn, and consider it important to get to grips with the scheme risks as they are assessed. As a result, they are clear in their instructions that they want to be involved in building their IRM framework and, to save on costs and expenses, after it is has bedded in they intend to take on responsibility for running it themselves.

Guidance: It may be a good use of limited resources for trustees to seek help in setting up the IRM framework so they can run it subsequently.

Example 3: IRM governance

The trustees already employ a chief risk officer as well as separate sub-committees for funding (including employer covenant) and investment matters. The trustees are mostly content with their existing structure and how it operates. However, they decide that putting in place an IRM framework affords an opportunity to better co-ordinate the work of these committees by modifying their existing governance structure.

Having considered several alternative structures, they decide to change their governance arrangements slightly. In future, the heads of each sub-committee, together with the chief risk officer, will be jointly responsible for providing an update on IRM to each quarterly meeting of the full trustee board.

The chief risk officer will provide support to each of the committees to ensure consistency of approach. The expectation is that joint responsibility for the IRM update will prompt each sub-committee head to share knowledge between them so that a considered, overarching message will be delivered to the trustee board.

Guidance: The introduction of IRM provides an opportunity to review governance structures, so that IRM can be co-ordinated and operated efficiently in the scheme’s particular circumstances.

23. Effective governance helps the trustees and employer not only to focus how they spend their time but also to make the best use of adviser resources in managing the scheme against important risks. For example, trustees should ask each adviser to take into account, and seek to ensure that their advice is consistent with, the work of the trustees' other advisers. This does not necessarily mean all advisers must agree on all issues, rather that their advice should have the same starting points for consistency of approach.

24. Advisers who work well together should be better able to help trustees make good decisions. Trustees should therefore consider taking steps to build relationships between their advisers, making clear an expectation that the advisers will work collaboratively. This may involve taking measures to address contractual and confidentiality issues the advisers have.

Example 4: Advisers working together

The scheme trustees have appointed actuarial, covenant and investment advisers from different firms. They want the advisers to work well together, and the advisers recognise that it is important for them to build relationships with each other as part of this process. The trustees make clear to each adviser that they expect them all to liaise with each other when preparing specific pieces of advice for which the others’ input is relevant, and also more generally so that each is aware of pertinent developments in the others’ thinking on matters affecting the scheme. They reach appropriate agreements with their advisers regarding how the short term costs of this investment in relationship building will be repaid over time by more targeted advice based on a better, more rounded understanding of the scheme’s position.

Guidance: Setting clear expectations for adviser behaviour and engagement, and making an upfront investment in relationship-building, should be repaid over time in more relevant, targeted advice.

Example 5: Advisers working together

It has become clear to the trustees that their advisers do not always use consistent modelling assumptions when producing their advice. This is unhelpful and confusing because, for example, changes to investment strategy may imply changes to the funding assumptions and vice versa. The trustees explain to their advisers that they need confidence that decisions they make in one risk area make sense in the context of the others.

To help resolve this, the trustees arrange an early meeting attended by their covenant and investment advisers and the scheme actuary. At this meeting they explain their overall strategy and instigate discussion on possible modelling assumption approaches stressing the need for consistency.

The advisers (and trustees) also agree that in future they should allow each other sight of the advice they provide for the trustees, as well as being available for further joint meetings or teleconferences as necessary.

Guidance: Trustees may need to support the advisers initially to co-ordinate their work and use consistent assumptions.

Key principles/questions for consideration

In summary, when considering an approach enabling them to manage risk in an integrated manner key questions for the trustees are:

- Who co-ordinates the process?

- How will the employer and trustees work together?

- How will the trustees empower advisers to work together?

- Are appropriate decision-making and reporting processes in place?

Step 2: Risk identification and initial risk assessment

25. The trustees should start from the scheme’s current position and examine the scheme’s current risks. The scheme’s current position should reflect the trustees’ funding and investment strategies already in place to meet the scheme objective. IRM risk assessment is then developed from this point. Its delivery will normally require close working between the trustees and their advisers.

26. It is important for trustees to have an understanding of the employer covenant as well as the scheme’s funding and investment positions before they take decisions which affect the scheme’s funding. They will achieve this understanding through advice and analysis, some of which is mandatory[3]. From this advice and analysis, the trustees should know the range of material risks and the drivers including:

- the risks associated with:

- the assumptions used to calculate the scheme’s technical provisions and any recovery plan[4], and

- the investment strategy and Statement of Investment Principles[5] together with

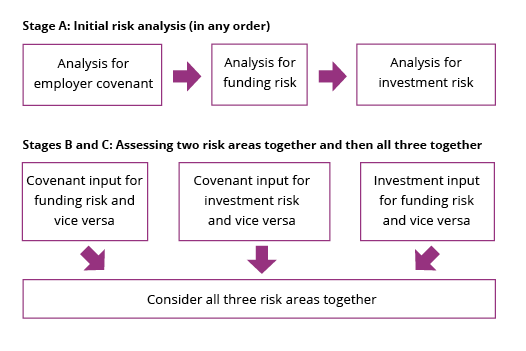

- an awareness of the risks associated with the employer covenant[6]

27. This advice and analysis is likely to focus on each element (funding assumptions, investment strategy and employer covenant) separately. The IRM approach takes this analysis further by examining methodically, and on a consistent basis, how the risks identified as significant for each element individually also impact upon the other two, and thus their overall effect on the scheme and employer. Some of these risks may impact in the same or a similar way; others may not have any wider impact. Additional risks may also be identified from this exercise. Trustees can then understand the extent to which risks are interdependent and their sensitivities, as well as their overall likelihood and potential impact if one or more occur.

28.The order in which the three fundamental DB scheme risks and the corresponding relationships between them are considered is less important than ensuring IRM is performed. However, it is best to start with the employer covenant assessment including appraisal of the reliable level of cash flow generation by the employer to determine the extent to which it can underwrite the risks to which the scheme is exposed. As such, for illustrative purposes, this guidance assumes that this approach will be followed.

Considering risks individually

29. Initial risk analysis and scenario testing should be completed for the employer covenant[7] to establish:

- the scenarios in which material risks arise

- how those scenarios arise

- the probability of them occurring

- what the impact of these material risks could be

30. Initial risk analysis and scenario testing should then be completed to answer the same questions separately for funding risk and investment strategy risk, in either order.

Considering risks bilaterally

31. The findings from the initial covenant risk assessment can then be related to the corresponding assessment input for funding risk and investment risk in turn (in either order) asking the following questions:

- Does the analysis reveal any causal links and/or any interdependencies? If so, how do risks from these interdependencies/relationships arise and how likely are they?

- What is their impact likely to be? More specifically (if relating covenant risk to the other risks), how do the identified covenant risks impact the scheme’s funding and investment strategy and what is the expected outcome from these risks?

- Is there a concentration of risk which affects one or more areas? If so, how remote is this concentration?

- Do significant risk themes (for example, market and economic or systemic) emerge?

- Are the scheme’s and employer’s risk capacities sufficient to cover the likely risks?

Example 6: Assessing employer risk

Previously when assessing investment risk the trustees have looked at the likelihood of the employer meeting its business plans to assess the employer’s risk capacity. They then reasonably assumed that it had good prospects and risk capacity.

When the trustees undertook a more detailed review under their IRM approach they asked the investment adviser to look at the most likely economic events that could impact on the investments and the reasons for them. This enabled the trustees to identify whether there was some material sensitivity to particular economic scenarios. In order to assess the concentration of risk the trustees then asked the covenant adviser to assess how the employer covenant would look in the same set of economic scenarios. They identified that there was a particular concentration of risk in one of the economic scenarios that could have an impact on the employer covenant as well as the scheme’s investment strategy.

Although it was amongst the least likely of risks, its impact could be substantial. Immediate risk reduction was not needed but the existence of the risk informed the trustees’ and employer’s approach to risk monitoring. Consequently, the trustees and employer agreed that this risk should be monitored closely and put in place a contingency plan that would enable them to act quickly if either the likelihood of the risk occurring increased or the estimated impact became more severe.

Guidance: Integrated risk assessment using consistent assumptions can identify meaningful concentrations of risk (in this case between the investments and the employer covenant) that individual analysis of each principal risk element may overlook.

Example 7: Assessing employer ability to underwrite investment and funding risks

The trustees’ covenant assessment has identified that the employer can be expected to generate £5m of free cash flow each year, of which around £2m could be realistically made available to the scheme (with the balance funding £1m each for debt repayment, capital expenditure and dividends). Current deficit reduction contributions (DRCs) are £1.5m per annum.

The trustees’ investment risk assessment highlights a one in 20 risk that the deficit could increase to a degree where they would need to increase DRCs to £2.5m per annum to clear it over an acceptable timeframe. The trustees are concerned that the employer covenant might not be able to support the increased level of DRCs over a sustained period.

However, by adopting an IRM framework, the trustees are able to work with the employer to reduce risk in their investment approach. The changed investment approach has a one in 20 risk of an increase in DRCs to £1.75m per annum to address the deficit over an appropriate period. This is a level of DRCs that the trustees are comfortable can be supported by the covenant.

Guidance: By assessing the investment risk in the scheme in conjunction with funding and its corresponding impact on the covenant, the trustees were able to find options to manage the risk. By working together, the employer and trustees were able to anticipate the potential impact of the risk and put in place an appropriate strategy to manage it.

32. Once the trustees have undertaken this assessment of covenant risk against the funding risk and investment risk, they should continue by examining the impact in the other direction, ie how their assessment of funding risk impacts the covenant risk and how their assessment of investment risk impacts the covenant risk. Following this, they should assess the funding risk against the investment risk (and vice versa) in a similar fashion.

Considering all risks together

33. The trustees should then complete their current strategy assessment by considering their findings for all three DB scheme risks together, re-addressing the questions under paragraph 31.

34. The following diagram illustrates the stages within this risk analysis and assessment.

Key principles/questions for consideration

Completing all of these stages should lead the trustees to form a more comprehensive risk assessment, which should allow them to answer the following questions:

- What are the material risks the scheme is exposed to, taking account of their impact and probability?

- How do these material risks impact on the scheme separately and together in qualitative terms and, where proportionate, quantitatively?

- Which are the highest priority risks?

- What does this analysis reveal about the totality of the risks that the scheme is running?

- What does this analysis reveal about the scheme’s and the employer’s risk capacities?

- What does this analysis reveal about the scheme’s and the employer’s risk appetites?

- Is any individual risk or the totality of risk greater or less than the trustees’ and/or employer’s risk appetites?

- What risk mitigation measures are available?

- What would the effect of these mitigations be on the scheme’s technical provisions and any recovery plan?

35. The trustees’ comprehensive risk assessment should equip them to open up dialogue with the employer on how best to deliver their overall strategy. This dialogue will be aimed at settling an agreed view of scheme and employer risk capacity and risk appetite by answering the following questions.

- Does the employer agree with the trustees’ assessment and prioritisation of the risks being run?

- Does the likelihood and impact of these risks fall within the trustees’ and the employer’s risk appetites?

- Do the trustees and employer agree that any action is needed to bring the scheme back in line within their risk appetites? What should this action be? Alternatively, should the risk appetites themselves be changed?

Example 8: Benefits of comprehensive, co-ordinated risk assessment

Scenario A

An employer is part of a group that is involved in the house building trade, supplying raw materials for construction as well as building and selling properties. The employer covenant is reliant on the performance of the employer in the property market and the scheme’s investment portfolio has a significant level of exposure to property assets.

Following discussion between the trustees’ investment adviser and covenant adviser they agree that this strategy could 'double-up' the risks associated with property markets. If the property market went into decline it is possible that the scheme’s funding level would decrease at a time when the strength of the employer covenant is weakening and the availability of additional contributions to the scheme becomes limited. Together, there could be a significant risk to members’ benefits. By sharing information and considering any shared exposure to risks between the covenant and the scheme’s investments, this scenario can be avoided.

Scenario B

The employer is part of an international group. Part of the group's core and lucrative business is in successfully developing opportunities in emerging markets, and the strength of the employer covenant is closely linked to success of these opportunities. Through comprehensive covenant advice, the trustees are aware of this and have a detailed covenant monitoring plan in place.

The employer's own business is mainly conducted within the European Union and the investment committee has never considered the sensitivities of the wider employer group when considering the investment strategy. Co-ordinating the investment and covenant sub-committees allows the trustees to make sure important information is shared. As a result, the investment sub-committee is aware that investing significantly in emerging markets might produce too much concentration of overall risk for the scheme and takes steps to ensure this risk is managed by diversification of scheme assets.

Guidance: Comparison of the covenant and investment risks may show that there are common drivers of both, revealing concentrations of risk that individual analyses would overlook.

36. It is essential that the employer understands the potential impact of the risks identified by the IRM analysis, for example the effect on its business plans of the corresponding increases in scheme contributions. This will allow it to evaluate that impact and compare it to its risk appetite. The employer can then work with the trustees on suitable risk management plans. It will also help to maintain visibility of the scheme’s financial position for the employer’s own investors. Further, an understanding of the employer’s risk appetite and circumstances helps inform the trustees’ own risk appetite and any risk management strategies proposed.

37. The trustees and employer will not necessarily have the same risk appetite. Where differences of risk appetite exist, it may be possible to structure a solution which meets the risk appetites of both, for example by contingency plans which introduce extra risk capacity.

Example 9: Addressing a mismatch of trustee and employer risk appetites

An employer performs long term infrastructure projects for governments and large multi-nationals. The employer has a good level of certainty over its future cash flows, allowing it to plan for the long term, and has a solid asset base.

Recently, the employer has won a large number of contracts and its performance has rapidly improved. Looking to capitalise on this improvement, it has the desire to list on the stock exchange, and as such is keen to minimise the potential for volatility in the cash flows of the business. Consequently, the employer has a limited risk appetite, and does not think that it has the capacity to take on an investment approach that carries a higher level of risk. The employer has not shared this with the trustees and thinks that by being prudent it is acting in the best interests of the scheme.

The trustees have been advised by their covenant and investment advisers that, due to the significant improvement in the employer’s performance, the employer covenant would be strong enough to support a greater level of risk than that currently favoured by the employer. The trustees agree and think that whilst the business is performing strongly this might be the optimum time to take greater investment risk, with the expectation that the deficit could be eliminated over a shorter period of time. The trustees have the appetite for an increased level of risk due to the immaturity of the scheme and are aware that some of the employer’s contracts expire before the end of the existing recovery plan. As a result, they are keen to plan for the future with any increase in risk backed up by contingent support from the employer (while there are unencumbered assets available), increasing their capacity to manage risk in a downside scenario.

The employer and trustees had not been fully aware of each other’s objectives or appetite and capacity for taking on extra risk. Together with their advisers, they analyse the outlook for the business and share their concerns. It becomes apparent that they can achieve their objectives whilst being conscious of each other’s risk appetites and risk capacities. Together, they agree to gradually increase the investment risk in the scheme and for the employer to provide a fixed charge as security. This solution maintains the existing cash flows from the employer whilst improving the security to the scheme at the same time as seizing the opportunity to try to clear the deficit over a potentially shorter period of time.

Guidance: Understanding the trustees’ and employer’s risk appetites and risk capacities generates productive discussions and allows a solution to be reached that is in the interests of both parties.

In this instance, the strong, improving covenant and contingent asset (risk capacity) supports a solution, putting in place protections for the scheme in the event that a downside scenario occurs. The increased level of risk accepted in the investment strategy (risk appetite) allows the employer to maintain the existing level of funding to the scheme and could enable the deficit shortfall to be recovered over a shorter than expected period of time.

38. As the IRM approach is iterative, risk identification is not a one-off exercise. The trustees and employer should consider repeating the risk assessment at intervals (that are proportionate to the size and circumstances of the scheme) to determine whether new risks or opportunities can be identified. Putting in place contingency plans and engaging in risk monitoring will assist in determining how frequently to undertake the risk identification exercise.

Footnotes for this section

- [3] See the DB funding code, covenant guidance and investment guidance.

- [4] See sections 222 and 226 of the Pensions Act 2004 and paragraphs 117 to 150 of the DB funding code.

- [5] See section 35 of the Pensions Act 1995 and paragraphs 88 to 98 of the DB funding code.

- [6] See paragraphs 61 to 75 of the DB funding code.

- [7] See the covenant guidance.

Step 3: Risk management and contingency planning

39. This analysis of the current position, risks and risk capacities enables the trustees and the employer to know whether they are comfortable with the current investment and funding strategies in light of the available employer covenant and scheme circumstances.

40. However, IRM does not stop with initial assessment of risk. Actions to manage risk may need to be taken, both now and in the future. Working with the employer, the trustees need to develop their IRM approach by adopting the following:

- Applying risk management strategies now (if applicable)

Having assessed the current position, the trustees may have concluded that the scheme is currently outside their or the employer’s risk appetites. They should therefore work with the employer to examine ways of strengthening the employer’s covenant, or modifying the funding and investment strategies, to bring the scheme back within the relevant risk appetite. The trustees should use the approach they adopted to review the scheme’s current arrangements to analyse possible and reasonable alternatives, illustrating their risk and return in different environments and their suitability. This might lead the trustees to modify their overall strategy for meeting their scheme objective. In any event, they should select and implement the most appropriate available funding and investment strategies for their scheme.

- Developing contingency plans for how to deal with material risks as they emerge in future

Having taken steps (if applicable) to bring the scheme within the trustees’ and employer’s risk appetites, the trustees and employer should develop a shared understanding of what actions they may take should their risk appetites be exceeded in future. This is essential to enable action to be taken swiftly and effectively to reduce or manage the level of risk acceptably should this occur. This involves discussions between the trustees and the employer when putting the IRM approach in place to understand:- how they would know that the covenant risk, investment risk and/or funding risk had exceeded risk capacity levels (for example by monitoring appropriate risk indicators, discussed below under Step 5: Risk monitoring)

- the actions that could be taken if required

- what effect these actions would have on the employer covenant, the funding deficit and assumptions (including those used for calculating scheme technical provisions and any recovery plan) and the investment strategy, and whether these actions are sufficient to manage risk to an acceptable level

Key principles/questions for consideration

- Risk management and contingency planning addresses these questions:

- What steps, if any, can or should be taken now to manage scheme risks?

- How effective are any scheme risk controls currently in place? Are they acceptable or can they be improved?

- How effective are the proposed new scheme risk controls expected to be?

- What adjustments could the trustees take to put the funding back in line with the trustees’ risk appetite to meet the scheme objective and restore an acceptable balance of risks if they needed to? If none, would the employer be able to contribute more to the scheme to manage the material risks?

- If there are no adjustments that could be made within the scheme or if the employer would be unable to contribute enough to the scheme to manage the risks if they materialised, is it possible to put in place contingency plans to cover any material risks?

- How quickly can these adjustments be made? If appropriate, are there other adjustments that would be quicker to implement, albeit less effective?

- Are these contingency plans sufficiently clear and substantial?

Example 10: Appropriate strategy selection and contingency planning

The employer and trustees have a strategy to move the scheme over a number of years to a funding position which would require little further reliance on the employer’s covenant. This involves a gradual and opportunistic de-risking approach.

Due to its business plans, the employer is sensitive to any increases in contributions and wants to ensure that the likelihood of the need to increase scheme contributions is kept within an acceptable range.

As part of the IRM assessment, the employer and trustees work together to establish what the likelihood is (absent any other steps) of needing to increase the employer contributions given the current investment strategy and to compare these to the employer’s and trustees’ risk appetites. The IRM assessment reveals that the scheme as it is currently being run has too great a risk of exceeding the trustees’ risk appetite.

Together, the employer and trustees agree to put in place safeguards so that if the investment returns underperform in any one year the employer will provide a pre-agreed amount of additional contributions to the scheme and if they underperform in consecutive years the employer will provide security to the scheme over a pre-agreed fixed asset. This proposal will enable the employer to remain within its business plans.

In the years following, the investment strategy performs as expected until a sudden dip in the equity markets. As a result of the IRM framework and pre-agreed triggers, the employer had been able to prepare for such an event and react to it quickly. The scheme receives additional contributions in the first instance and subsequently security over the agreed fixed asset so that if the downturn continues it has protection.

Guidance: An IRM assessment can identify future risks and put in place a strategy to manage them. This can enable both the employer and trustees to achieve their objectives without taking on unnecessary amounts of risk and put in place an action plan in case they do arise.

It is important that any triggers set as part of an IRM framework are practical and realistic so that in the event of the trigger occurring both the employer and trustee are committed to the agreed action(s).

41. It may not be possible for all risks to be managed. The trustees’ IRM framework should enable them to establish whether any unmanaged risks remain, assess how these sit against the trustees’ and employer’s respective risk appetites, and monitor them on an ongoing basis. Where a material risk is not covered by a firm contingency plan, it would be good practice for the trustees and employer to commit at the outset that they will engage in discussions about how to monitor and manage these risks.

42. Keeping track of the material risks can also mean that the trustees and employer do not miss valuable opportunities to lock in improvements. For example, if the investment strategy outperforms the funding assumptions, this might allow the trustees to adopt a lower risk investment strategy or buy out some current pension liabilities, all in line with their IRM approach.

Example 11: Taking advantage of upside opportunities

An employer is growing and, due to a surge in demand for its products, has had a number of successful years. The employer is keen to take advantage of its success and invest in capital expenditure to continue to fuel growth and plan for the future.

The trustees, although currently happy with the level of risk in the investment portfolio, are concerned that in the future the level of risk in the scheme might exceed their risk appetite and would like to take steps now for additional cash to be used to reduce the level of risk.

The trustees and employer negotiate how best to use any additional cash. The employer appreciates the trustees' concerns that the long term future is unknown, but provides detailed information to the trustees regarding its short and medium term forecasts to assure them that the growth of the business is sustainable. Due to investment in sustainable growth, the employer cannot, for the time being, commit to a higher level of deficit recovery contributions than those agreed under the current recovery plan. The trustees understand this but make clear that the scheme should still share in any additional cash generated.

Having understood each other’s position, the employer and trustee agree to put in place an IRM framework, which includes a mechanism to utilise any future free cash flow taking into account each other’s risk appetites. The mechanism provides for equitable use of free cash flow; half to be invested in capital expenditure and the other half to be placed in an escrow account for the scheme. Between them, the trustees and employer agree appropriate triggers for the escrow account so that, in the event of the existing investment strategy underperforming, the cash would be released to the scheme, but if the investment strategy performs as planned the cash would be returned to the business.

The trustees are comfortable maintaining the same level of investment risk in the scheme, having seen the employer’s forecasts and knowing that sufficient funding would be set aside to protect the scheme in the event that it would be needed. The investment in capital expenditure should be covenant enhancing, which is in the interests of the trustees. It contributes to the employer’s objective and the employer also knows that the cash in escrow could be returned to the business. Setting aside cash in advance can help an employer to plan for the future knowing that it is potentially less likely to have to increase the level of future cash flows into the scheme.

Guidance: IRM should not only take into account the impact and consequence of downside risks, but also enable the stakeholders in the business to share in its success and upside opportunities.

A pre-agreed mechanism to share upside can ensure that benefits for both the scheme and the employer are made available quickly.

Step 4: Documenting the IRM framework and decisions reached

43. Clear documentation of trustee decisions is part of good scheme governance, not least because poor record-keeping can lead to poor decision making, significant additional costs and reputational damage.

44. The great benefit for trustees in recording their thinking and the decisions made is that this should distil matters down to a series of key points so they retain a clear overview concentrating on what is important and why. A better understanding of risks leads to better decisions.

45. Documenting the agreed IRM framework should not involve trustees spending disproportionate time and resources. There is merit in using existing documents as much as possible (for example, monitoring and contingency plans might be contained within the scheme recovery plan).

Key principles/questions for consideration

When documenting their IRM framework trustees should consider how they:

- articulate their overall strategy

- record the assessments they have undertaken

- record the decisions they made leading to the actions they have put in place (this may include an outline of alternatives considered and why they were discarded)

- where decisions have required particular judgement in the face of uncertainty, describe fully the process followed to make that decision, highlighting the differences that variations in the key assumptions might have made

- record the input from and agreements reached with the employer

- retain and retrieve the advice they have received in putting in place the IRM framework (for example, they might keep a short summary of this advice which includes a reminder that the decisions are recorded in the Statement of Investment Principles, the Statement of Funding Principles or in relevant trustee meeting minutes)

- set out how they will monitor the material risks and put in place any contingency plans

Step 5: Risk monitoring

46. Treating the assessment of risk as a triennial, valuation-related hurdle to overcome will limit the benefits of the IRM framework. Circumstances can change quickly and significantly. Hand in hand with their contingency planning, trustees need to focus on how the important and material risks are developing. Frequency of monitoring depends on the materiality of risks and on scheme resources. If risk levels approach the agreed risk appetites, the frequency of monitoring should be increased correspondingly. As a minimum, trustees should consider conducting high level monitoring at least once a year.

47. Monitoring all the material risks, together with appropriate contingency planning, will allow trustees to respond quickly and effectively should the risks emerge. It will also serve as a focus for future discussions among the trustees and between trustees and employer. For example a 'financial risk dashboard' could be used to monitor the key measures (such as risk parameters and performance indicators) for the material risks.

48. In addition, more frequent monitoring allows trustees to respond quickly to take advantage of opportunities to lock in improvements. This might occur, for example, where the employer covenant strength has rapidly improved and the employer has more cash available than expected, some of which it wishes to use as an unscheduled contribution to reduce the funding deficit.

49. Monitoring triggers and their consequences should be reviewed on an appropriately frequent basis so that they can remain relevant to the position and performance of the employer and the scheme.

50. In the majority of situations it should be possible to base the monitoring on information that is already being produced. For example, covenant monitoring could be based predominantly on information which is already produced in the employer’s regular management accounts.

Key principles/questions for consideration

Trustees should consider:

- what risk measure will be set for each material risk

- how often these risks need to be monitored

- who will be responsible for monitoring these risks

- how these risks will be reported to the trustees (and with what frequency). Timeliness of information is vital but do the trustees need daily reporting or will quarterly or even annual reporting be sufficient for some risks?

- what purpose the reporting serves. Is it simply for information, does it indicate the need for increased trustee watchfulness or does it require an immediate decision and action from them?

- how they will check for new risks and how frequently they will do this

- how they will identify and take into account any changes in the trustees’ and the employer’s risk capacities and appetites

51. The monitoring approach can set out the points at which an agreed measure or combination of measures will trigger action by the trustees. They should be informed by the material risks and significant risk themes, and be capable of giving clear signals for action relevant to those risks. The trustees’ advisers should be able to advise on suitable risk indicators and appropriate triggers for action for the scheme given its and the employer’s circumstances.

Key principles/questions for consideration

Areas in which possible risk indicators and associated triggers might be set include[8]:

- employer covenant performance metrics (for example, a change in profitability, cash flow or debt levels or reduced covenant visibility arising from corporate restructuring)

- employer investment in its business proceeding in accordance with previously agreed metrics (for example, where the trustees have agreed to accept greater risk in order to facilitate employer investment in sustainable growth, a change in the employer’s previously agreed plans or the failure of these plans to deliver anticipated improvements to the covenant)

- realisation of anticipated growth in the employer’s business

- conflicting demands on the employer covenant from other schemes

- funding level and its volatility (for example, scheme funding deteriorating (or improving) to a specified level)

- longevity risks, especially if just a few members account for a significant proportion of the benefits payable

- scheme liquidity needs as it matures (for example, scheme cash flow imbalance threatening the need for enforced asset sales to meet benefit payments)

- scheme liquidity needs to pay significant, or significant numbers of, transfer values

- interest rate changes

- inflation levels

- investment market movements

- scheme investment performance (for example, a specified level of scheme investment under-performance or over-performance over a stipulated period, whether in relation to the whole investment portfolio or in relation to a specific subset of investments, such as equities)

- scheme asset values

- investment counterparty risks

Example 12: Monitoring

The trustees have identified that the scheme’s current investment strategy and funding level present risks given the relative weakness of the employer covenant available to support them. Although these risks are within the employer’s risk capacity, the trustees would prefer to adopt a lower risk investment strategy along with higher technical provisions and a shorter recovery plan, leading to higher employer contributions. However, the employer has plans to invest in the sustainable growth of its business and has made a strong case to the trustees that this investment will strengthen the covenant over time.

The trustees review the employer’s proposals carefully and seek advice on whether the covenant is strong enough to support the increased risk. They conclude that it is (but only just) and agree to support this employer investment by adopting a higher risk investment strategy, lower technical provisions and a longer recovery plan. In doing so, they expect to see that this investment is duly made in accordance with the budget and timescales the employer has set out and that the employer covenant does improve as envisaged. They also agree that, once employer performance reaches agreed levels, the contributions to the scheme will increase, facilitating de-risking. While continuing to monitor scheme investment performance and scheme funding levels, they are also particularly careful to keep the employer’s investment activity in view to ensure that its level and timing is on schedule. They also monitor the employer’s covenant to be satisfied that this improves as expected as the investment bears fruit.

Since employer covenant improvement may not occur as expected, possible agreed actions might range from employer sharing of confidential management accounts to explain the reasons for delay, to a review of the scheme investment and funding strategies, including discussion as to alternative methods of employer support and/or reducing the investment and funding risk levels.

Guidance: In a situation where the trustees have agreed to higher levels of scheme risk to facilitate the employer’s growth plans, it is important to put a comprehensive monitoring framework in place with agreed actions should the risks and opportunities materialise.

Risk assessment tools

52. When trustees consider an IRM approach, they should bear in mind the principles of proportionality. Sophisticated risk assessment tools may be time-consuming and costly, and not necessary if the risks facing the scheme are simple and straightforward. Trustees may wish to seek the help of their advisers on whether a detailed risk analysis and IRM approach would be beneficial, bearing in mind that the trustees retain responsibility for the overall IRM approach and its application. It may be helpful to conduct a basic risk assessment first, to inform this judgement.

Key principles/questions for consideration

The following points are important for trustees to consider when deciding on the approach to follow.

- whether the individual risks faced by the scheme large in terms of their likelihood and impact. Are they complex, for example driven by multiple factors?

- whether they are likely to be inter-related to a significant degree

- if they need to conduct sophisticated modelling in order to understand them

- if they can satisfy themselves that the approaches recommended by their advisers are proportionate and appropriate to the scheme’s circumstances

- that they should make an informed decision on the best IRM approach to adopt having ascertained the potential costs and established from their adviser what outputs the testing or modelling being offered will provide (including its limitations)

53. In the appendix, some of the more common risk assessment techniques currently used are outlined for illustrative purposes.

Footnotes for this section

- [8] See also section 3 of the covenant guidance.

Appendix

Possible risk assessment approaches

54. This appendix sets out a variety of approaches to risk assessment that trustees might find useful. It is not intended to be an exhaustive list. For those trustees and employers who have not undertaken a risk assessment before, it is likely to be most valuable to start with one of the less complex approaches (such as stress testing) and, as techniques become more familiar, progress through different approaches to more complex analysis (stochastic modelling and reverse stress testing).

55. Some trustees and employers may already employ different risk assessment techniques. The relevance of the different approaches to any particular scheme will depend on the scheme’s circumstances; other techniques may be equally or more appropriate for a scheme’s particular requirements.

56. The use of a range of techniques may help with the identification of different risks that might have been overlooked by following a single approach or be too unlikely to warrant further scrutiny. The identification of risk followed by discussion and analysis is key, followed up where necessary with appropriate negotiation and action. In all cases, employers and trustees will need to exercise judgment as to what is reasonable and proportionate for the scheme.

Stress testing

57. Stress testing involves identifying variables that affect the finances of the scheme or employer, changing the values for those variables, and seeing what effect this has. This helps identify which variables are most important, through their impact on covenant, funding and investment.

58. Stress tests are a type of forward-looking 'what if' analysis. Applying them to each variable individually at a single point in time can enable the trustees to see which variables individually have the most potential impact on the scheme’s position.

59. Although stress tests often focus on financial market scenarios, considering a wide range of variables and possible values for them is important. By working together, both the employer and the trustees can increasing their understanding of the key drivers and influences on the scheme and the employer.

Example 13: Stress testing

The employer covenant assessment, funding strategy and investment strategy might all be based on the assumption that price inflation will be 2% per annum over the long term.

A stress test of this variable would involve letting the inflation assumption take a range of different values, higher and lower, and seeing what effect this has on the covenant, the liabilities, and the value of the scheme’s assets.

Using the inflation example, an increase from 2% to 3% per annum might have more of an impact on liabilities than a further increase from 3% to 4% per annum, if the increases to some pensions in payment are capped at 3%. However, the impact on the covenant might be progressively worse as inflation increases beyond 3%.

From a covenant perspective, the employer might consume materials or produce goods that are particularly sensitive or insensitive to changes in price inflation. For example, luxury goods are typically relatively insensitive to changes in inflation, whereas some sectors such as utilities or transport can be regulated so that their prices are linked to changes in inflation. This might have a greater or lesser effect on revenues and costs and consequently the employer covenant.

60. The levels of stress applied to each variable can be chosen to reflect how likely the trustees and their advisers think it is to happen. The trustees might consider that there is a one in 20 chance of long term inflation being more than 3% per annum and factor this into their conclusions.

61. Stress testing can be relatively simple to apply. It can provide an indication of the material risks the scheme faces, and is a good starting point for more sophisticated techniques.

Scenario testing

62. Scenario testing is a development of the basic stress-testing of individual variables. It involves stressing the values of several variables simultaneously at a single point in time, in a way that is self-consistent and reflects a chosen economic scenario. It considers the impact on employer covenant, funding and investment of a sudden change to different economic circumstances. Stress testing, in contrast, considers the impact of adverse movements in individual variables or 'stresses' separately from any particular economic scenario.

Example 14: Scenario testing

Employers and trustees could begin their analysis by considering typical economic scenarios such as boom, slowdown, recession and recovery conditions. Looking to the past might also provide suggestions for scenarios that could occur again and help to estimate the impact of similar scenarios.

An example to illustrate scenario testing could be a significant fall in oil prices such as that in 2014. This scenario has various impacts and affects employers and schemes in many different ways. These could include but are not limited to the following:

- An increase in overall economic activity as the cost of production decreases for many UK businesses, especially for those that are heavily dependent on oil inputs (eg agriculture, transportation, and manufacturing). This could have a positive or negative impact on covenant depending on the type of business of the employer and its key customers and suppliers.

- In addition to an impact on covenant there might be an impact on investment performance as the value of some equity holdings or corporate bonds could change; some may benefit whereas as others such as those in the oil and gas sector may decline.

- An increase in economic activity can boost employment and might lead to wage inflation; it can prompt greater levels of investment by employers; and if household incomes rise it could increase consumer spending which is often positive for sectors such as retail, leisure and transport.

- A decrease in oil prices and consequently petrol prices, a component of both the consumer price index and the retail price index, can have a temporary deflationary impact.

63. The results of basic stress testing should influence the choice of scenarios analysed, so as to focus on the most relevant ones for the scheme. For example, if the stress testing suggests that the scheme is particularly exposed to changes in foreign exchange rates, then scenarios in which changes to foreign exchange rates occur should be considered and given appropriate weight.

64. Some scenarios may be especially relevant to the employer’s business and have a potentially significant impact on its covenant. The scheme’s advisers should be able to suggest and put together appropriate scenarios, and advise on their likelihood.

Scenario projections

65. The approaches set out above consider the effect of an immediate change in conditions, as part of either a stress test or an economic scenario, on the employer covenant and the scheme’s assets and liabilities. However, it is important to understand how the scheme’s finances may evolve in future years. Projections into the future give more insight than just considering immediate changes.

66. In order to make these projections, the advisers may use models of the employer and the scheme. Projection models vary in points of detail, and some can be quite complex. The models should take into account the scheme’s liability profile and its proposed deficit recovery contribution patterns to assess the extent to which the scheme would have the assets needed to pay benefits as they fall due and the extent to which employer covenant support would be required and available.

67. The projections can be run across a range of economic scenarios that are relevant to the scheme’s circumstances. The difference from scenario testing is that the modelling covers the scheme’s finances over a number of years, not just the impact of immediate change. This enables a more nuanced range of relevant economic or market circumstances to be considered.

68. It is difficult to predict scenarios that could affect schemes and employers over a 5, 10 or 20 year period. However, consideration of these can reveal qualities or factors about the employer or the scheme that had not been thought of before and can prompt a higher level of engagement between trustees and employers in the assessment of future risk.

Example 15: Scenario projections

The scheme actuary advises trustees that, based on projection modelling, the scheme is expected to mature rapidly over the next few years, becoming strongly cash flow negative in seven years’ time. The trustees would then need to sell assets to meet benefit payments.

A relevant scenario projection in this case might be a severe downturn happening in five years’ time and lasting over a further period of five years. Coming at a time when the scheme is strongly cash flow negative, this might have a more serious and lasting impact than a similar scenario where the downturn happens in the first five years when cash flow is positive and assets do not need to be sold when markets are down.

Examples of trends that might help illustrate scenarios projections that could impact a scheme or employer into the future could be, but are not limited to the following:

- Global economic dynamics – an increase in global mobility and increasing focus on emerging markets. Changes in customer tastes and methods of transacting.

- Global demographic shifts – a growing but also ageing global population.

- Urbanisation – greater demands on infrastructure, transport, healthcare, education and housing.

- Political and cultural relations – a global community increasingly cooperating and sharing ideas, or some parts of the world having greater potential for conflict.

- Climate change – changes in demand for food and natural resources, such as water and energy.

- Technological innovation – the rise of digitalisation and connected devices.

Trends such as these could have an impact on both the employer covenant if events are positive or negative for an employer’s business, and/or scheme investments, such as through equities or corporate bonds.

Linking this to the example above, an employer and trustee could consider whether these trends will occur, when and the extent to which these trends are likely to impact their particular business or scheme.

Stochastic modelling

69. Stochastic modelling is a more sophisticated projection modelling approach which starts from the basis that future market conditions (eg investment returns, interest rates and inflation) are subject to a range of future uncertainties. It can be used to consider the risks involved in adopting complex investment strategies, or in situations where the risks facing a scheme are significant (for example where the scheme is significantly underfunded or the scheme is mature).

70. A stochastic model produces a fuller range of possible future scenarios for market conditions, and projects the scheme’s finances in each of these. The projections can then be examined to indicate the likelihood of particular outcomes according to the model used and assumptions made.

Example 16: Stochastic modelling

The trustees have asked their actuary to work with the investment consultant to examine the potential funding level of the scheme in 10 years’ time.

The investment consultant selects appropriate modelling assumptions, having discussed and agreed these with the actuary, and explains the key ones to the trustees. He states that his stochastic model shows that, for the scheme’s current investment strategy, the probability that the funding level in 10 years’ time will be above 100% is around 70%. His model uses 10,000 different scenarios and the funding level in 10 years’ time is above 100% in 7,029 of them.

He then goes on to describe this as being spuriously accurate, explaining further that this result is highly dependent on the model and assumptions used. However, examining different investment strategies using a common model and assumptions can help with choosing between them. He therefore shows the corresponding model output for a range of different investment strategies and helps the trustees work through the relative merits of each. The trustees decide that two of them are worth exploring further.

The investment consultant also explains that one of the key assumptions in his model is that, over time, bond market interest rates will rise further and faster than is implied by current bond market pricing, with the model introducing random variations around this central scenario. This is broadly consistent with the assumptions adopted for the scheme’s recovery plan. The trustees consider this and agree that it would be helpful for their understanding of risks to examine additional projections in which the central scenario is for bond yields to remain lower for longer, as predicted by current market pricing. This further analysis then helps them choose between the two strategies identified earlier, since one of them is expected to perform notably better in this environment.

71. Stochastic modelling is primarily a technique applied to pension scheme assets and liabilities. It can be used to help trustees understand by how much the funding level of the scheme could change over a set time period in number of reasonable downside scenarios, whether this level of investment risk can be supported by the scheme and what this might mean for employer contributions. This can provide a useful comparator for the scheme’s position and risk profile against the risk capacity of the employer and trustees.

72. Stochastic modelling is a useful method for comparing different investment strategies but it is highly dependent on the model and assumptions used. It is therefore important to understand the key assumptions and to consider the merits of plausible alternative assumptions.

Reverse stress testing

73. Reverse stress testing is a risk assessment technique which works backwards from an adverse outcome for the pension scheme and seeks to identify and aids understanding of the full range of scenarios and series of events which could have caused that outcome.

74. The types of outcome to consider might include, but are not limited to, being in a situation where even though the trustees make full use of the flexibilities available under the Part 3 scheme funding regime, it is impossible to set a realistic recovery plan to full funding within a reasonable timescale.

75. The sequence of events leading to this might, for example, comprise some combination of a significant weakening of the employer’s covenant, increases in scheme liabilities, reduced expectations for future investment returns and poor actual investment returns. The analysis for any particular scheme would look in more specific detail at why these events could have occurred, how they are linked and what their knock-on or compounding effects are for the scheme.

76. Working backwards can help capture a wider range of possibilities and circumstances than those typically contemplated in a classic stress test. Classic (forward-looking) stress tests, described earlier in this guidance, consider the outcomes achieved under a range of pre-determined scenarios and typically include financial market stress scenarios only. In contrast, reverse stress tests focus on a particular outcome and seek to understand a full range of scenarios, including financial and non-financial market stress scenarios, which could have caused that outcome.

77. Having used reverse stress testing to identify a broader range of risks to the pension scheme, the trustees should then assess their likelihood and importance. The trustees may then be able to take pre-emptive action as part of their IRM approach to improve outcomes and limit the impact that might otherwise occur where particularly negative scenarios have been identified. The identification of a wider range of risks should lead to a more informed debate about the risks the scheme faces, and the actions it is appropriate to take in respect of them.

Example 17: Reverse stress testing

The sponsoring employer of a poorly funded scheme has undergone a restructuring and is rebuilding its business around a new suite of products. The company believes that after an initial developmental period its profitability and free cash flow will significantly improve. It has proposed a recovery plan where the DRCs are low initially, and then increase significantly in anticipation of the improved free cash flow.

The scheme is mature and is currently disinvesting assets regularly to meet the excess of scheme benefit payments over investment income and contributions. A significant minority of the membership are entitled to enhanced early retirement benefits. In recent years however, these members have tended to work through to normal retirement age, and this has been reflected in the funding assumptions, which make no allowance for members retiring early with enhanced benefits.