A review of defined benefit (DB) pension schemes with valuation dates between September 2021 and September 2022 (Tranche 17 or T17 valuations).

Published: 25 May 2022

Introduction

This analysis of the expected positions of DB pension schemes with valuation dates between 22 September 2021 and 21 September 2022 (Tranche 17) gives further context to our 2022 Annual Funding Statement (AFS) but does not supersede it. The analysis is necessarily technical in nature and so is primarily aimed at a more technical audience than the main 2022 AFS.

In modelling the impacts of market conditions on schemes, we have made a number of approximations based on the high level and limited data we hold, which means we cannot take account of all scheme-specific characteristics. The method and simplifications we have made are contained in the methods, principal assumptions and limitations section. The position of individual schemes will vary depending on a number of individual factors, not considered here.

The strength of the employer covenant is a key consideration for trustees and employers when setting their funding strategies. In previous years’ analyses we have shown trends in potential employer affordability. This analysis was based on historic, publicly available information on profit, shareholder funds and dividend payments. Given the significant and uneven impact of the COVID-19 crisis on scheme employers, for many schemes, recent trends in employer affordability based on historic data are likely to be of limited use in assessing employer affordability today. Consequently, we have again excluded trends in employer affordability from this year’s analysis. We have also again excluded data showing segmentation of Tranche 17 schemes into the AFS categories (A to E) as this data is also based on historic assessments of employer covenant.

The remaining analysis is similar to the analysis carried out in previous years.

This material and the work involved in preparing it are within the scope of and comply with the Financial Reporting Council’s Technical Actuarial Standard 100. For the purpose of this standard, the users of this material are considered to be the trustees of the DB schemes whose funding we regulate, the employers who fund those schemes, and their actuarial advisers.

Summary

Market conditions and impacts on scheme funding levels

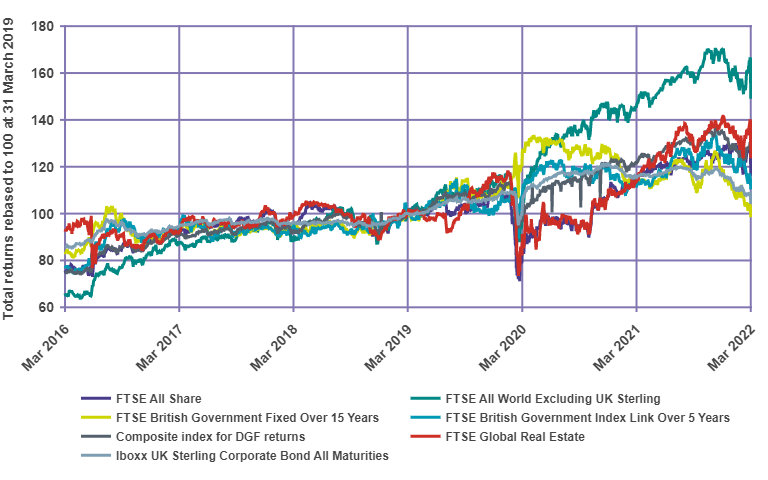

Our analysis shows that most major asset classes invested in by UK pension funds achieved substantially positive returns over the three years to 31 December 2021 and the three years to 31 March 2022.

For example, over the period from December 2018 to December 2021, the FTSE All World (excluding UK) Index returned +68% in sterling terms, and for the period March 2019 to March 2022 the return was +49%. The return on FTSE British Government fixed over 15 years index was +18% over the three years to December 2021, but -2% over the three years to March 2022 (see Table 1).

Nominal gilt yields were significantly lower at 31 December 2021 than they were three years earlier, whereas at 31 March 2022 nominal gilt yields were higher at the longer end of the curve (albeit lower at the shorter end). Real yields at all durations were much lower at 31 December 2021 than they were three years earlier, whereas at 31 March 2022 real yields were only slightly lower overall to what they were three years earlier (lower at shorter durations and slightly higher at longer durations than they were three years earlier). See Figures 1 and 2.

For the purpose of this analysis as at 31 December 2021 and 31 March 2022 we have assumed the liabilities are calculated using discount rates which have the same margin over gilt yields that they had at a scheme’s last valuation date. We have also made an allowance for the alignment of Retail Prices Index (RPI) to Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers' housing costs (CPIH) from 2030. Together with the change in gilt yields this means the technical provisions (TPs) calculated at a comparable effective date are likely to have grown over the three years to 31 December 2021 but stayed broadly similar in the three years to 31 March 2022. For the purpose of this analysis, we have not attempted to quantify the potential impact of COVID-19 on schemes’ mortality experience or assumptions. Nor have we considered what, if any, adjustment is appropriate to apply to the CMI 2021 projections.

In practice, the Russian and Ukrainian conflict, COVID-19 and Brexit may have impacted the strength of the employers’ covenant which should be reflected in the TPs. This has not been reflected in our analysis.

Overall, our modelling also suggests that schemes undertaking valuations at 31 December 2021 and 31 March 2022 will show improved funding levels from those reported three years previously and the current recovery plan (RP) will be on track to remove the deficit by the end date. See Figures 5a and 5b.

However, the position for individual schemes will vary greatly compared with our aggregate estimates. This variation will depend on scheme-specific inter-valuation experience, valuation dates, funding assumptions and investment strategies. For example, at 31 December 2021 schemes that had materially hedged interest rate and inflation risks appeared to have slightly improved funding levels compared to three years previous, compared to unhedged schemes. The position is less clear for schemes as at 31 March 2022 depending on their level of inflation hedging and inflation linkage in benefits. This variation in funding level is demonstrated in Figures 7a and 7b.

Implications for recovery plans and affordability

Our modelling shows that if Tranche 17 schemes all had 31 March 2022 valuation dates and were to retain their RP end dates, or for those schemes nearing the end of their RP make a modest increase in the RP length (to bring the length to three years), 68% of T17 schemes in deficit would be able to retain their deficit repair contributions (DRCs) at the same level or reduce them (see Figure 8), while just 1% would need to increase DRCs to more than three times their current level. Some of this latter group of schemes would need to increase DRCs by much more than this.

As mentioned above, in practice, the Russian and Ukrainian conflict, COVID-19 and Brexit may have impacted the strength of the employers’ covenant which should be reflected in the TPs. This has not been reflected in our analysis. Strengthening of TPs will increase the deficit and, if the RP end date is to be maintained, will lead to higher DRCs than our analysis shows.

In addition, DRCs may be limited by employer affordability, especially in the short term where employers have been materially impacted by COVID-19.

Market indicators

Scheme funding is sensitive to the impact of the changes in market conditions on schemes’ assets and the valuation of their liabilities.

Common valuation dates

The end of December and end of March are the most common valuation dates for schemes in this tranche. Therefore, we have concentrated on these dates in this analysis.

The 5 and 6 April are also common valuation dates. We have not presented analysis at these dates. However, market conditions at 5 and 6 April 2022 were similar to those at 31 March 2022.

Bond yields

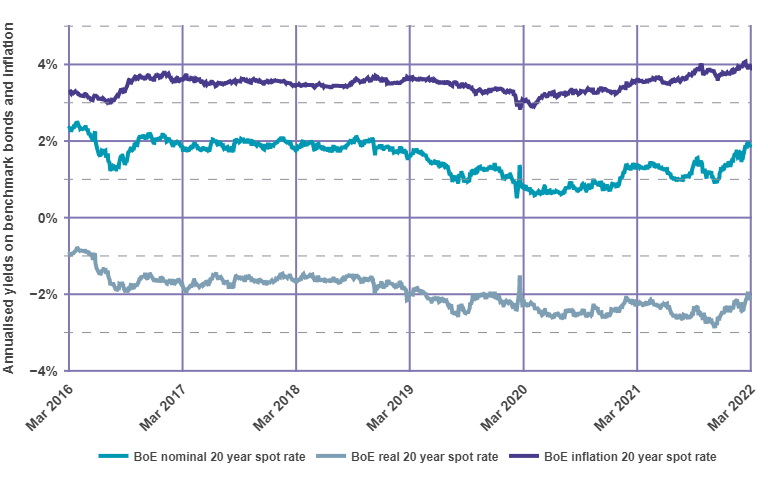

Figure 1 shows the Bank of England (BoE) estimates of nominal and real gilt yields and implied inflation as measured by the RPI at a 20-year duration at each date from March 2016 to 31 March 2022.

Figure 1: Benchmark yields

Sources: BoE, Refinitiv (financial markets data)

There has been a fall in gilt yields since March 2016. Long-term real gilt yields fell into negative territory in 2014 and have remained negative ever since. Nominal yields had fallen in the same fashion to the end of 2021 but both have since risen back to levels comparable with 2019.

Long-term market-implied inflation has remained mainly in the range 3%pa to 4%pa over the six-year period, although this has risen over the last 12 months.

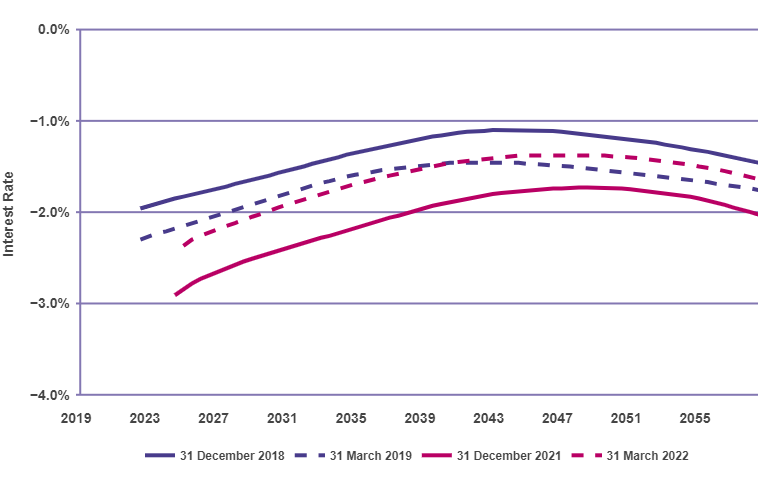

Figure 2 shows the real forward interest rates as estimated by the BoE as at the end of December 2018, March 2019, December 2021 and March 2022.

Figure 2: UK instantaneous real forward gilt curves

Source: BoE

The shape of the curve is reasonably similar at the four dates, however between December 2018 and December 2021 there was a significant fall in real interest rates along the whole curve. Between March 2019 and March 2022 there was a fall in real interest rates in the short end of the curve, with similar yields in the middle and a rise in real interest rates at the long end of the curve.

All other things being equal, we expect that if trustees use a discount rate to calculate liabilities that has the same margin above gilt yields at the previous valuation, most schemes as at 31 December 2021 will have a higher reported value for their liabilities than they were expecting, whereas their liabilities will be similar as at 31 March 2022.

Asset returns

Figure 3 shows total returns for a range of asset class indices since 2016. The returns have been re-based to 100 at 31 March 2019, so the chart shows the relative change up to and from that point.

Figure 3: Asset returns

Source: Refinitiv

Table 1: Total returns in UK Sterling from different asset classes over the three years to 31 December 2021 and 31 March 2022

| Index name (asset class) | Total returns over the period 31 December 2018 to 31 December 2021 | Total returns over the period 31 March 2019 to 31 March 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| FTSE All Share (UK equities) | 27.2% | 16.8% |

| FTSE All World Excluding UK Sterling (overseas equities) | 68.2% |

49.4% |

| Iboxx UK Sterling Corporate Bond All Maturities (corporate bonds) | 16.8% | 4% |

| FTSE British Government Fixed Over 15 years (fixed interest gilts) | 18.2% |

-2.2% |

| FTSE British Government Index Link Over 5 years (index-linked gilts) | 25.1% | 10.1% |

| Composite DGF index | 44.8% |

29.1% |

| FTSE Global Real Estate (property) | 41.6% |

24% |

Over the three years to December 2021, all asset classes shown above saw positive returns. Over the three years to March 2021 most assets classes shown above saw positive returns except for FTSE British Government Fixed Over 15 years which had a small negative return.

DB schemes

Funding position of DB schemes in aggregate

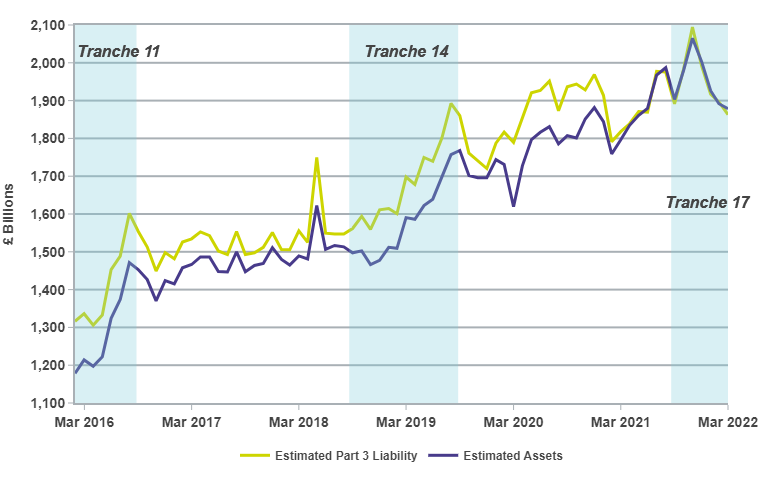

Figure 4 shows estimates of assets and liabilities (technical provisions) for all schemes in our regulated DB universe, based on rolling back and projecting forward the data we held at 30 September 2021 (rather than using historical data at historical dates). This is an aggregate analysis based on highly summarised data.

Figure 4: Estimated assets and liability positions of DB pension schemes

Sources: The Pensions Regulator (TPR) (scheme data), Refinitiv

Overall, the changes in market conditions and aggregate pace of schemes’ funding plans mean that deficits on a TPs basis as at December 2018 and March 2019 for the DB universe are expected to have turned into small surpluses as at December 2021 and March 2022.

Potential impact on scheme deficits in more detail

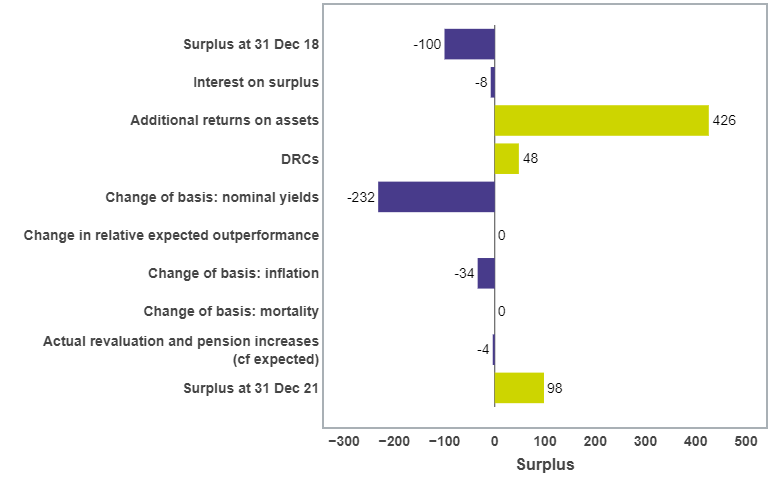

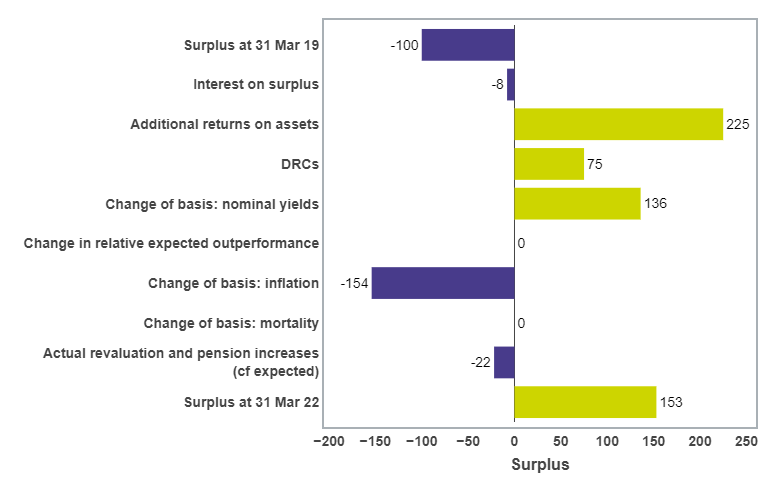

The analysis above showed how funding levels have changed for all schemes in the DB universe. This may not be representative of the tranche of schemes undertaking valuations now (Tranche 17). Figures 5a and 5b illustrate the key drivers in the change in deficit for all Tranche 17 schemes at the two most common valuation dates: 31 December and 31 March.

We have assumed that the discount rates that are used to calculate the liabilities of each scheme have changed since the previous scheme valuations, broadly in line with three factors:

- the movement in real and nominal gilt yields over the period

- the movement in investment portfolios from growth-seeking to matching assets

- a change in the expected return on assets above the gilt yield

As in previous years we have seen evidence of schemes investing in more matching assets. We have also considered how discount rates may have changed as a result of changes in expected returns on return-seeking assets since the previous scheme valuation and have seen a variety of views. For the purposes of this analysis, we have adopted a similar discount rate premium as at the previous valuation, resulting in a zero item in Figure 5a for ‘change in relative expected outperformance’ for 31 December 2021 and 31 March 2022.

In practice, schemes may use different approaches to setting discount rates and may also have different views now on prudent expected returns from the same portfolio than they had at the previous valuation.

When rolling forward valuations TPR has historically attempted to estimate how the “typical” mortality assumption will change tranche to tranche (and over the three-year valuation cycle). There are a variety of opinions over how to interpret excess deaths from COVID-19, and the weighting to apply to data for years 2020 and 2021 in respect of the CMI future improvement model also can now be chosen by trustees as part of the valuation assumptions. This means that at this stage it is difficult to predict how trustees will take account of mortality assumptions for the T17 valuation cycle, and hence we have made no allowance for mortality changes since T14 in our analysis.

For the purpose of this analysis, to estimate the level of hedging we use PV01 and IE01 data, provided along with a scheme’s asset data. If these aren’t available, we make an assumption based on the scheme’s asset portfolio as to the extent of interest rate and inflation hedging.

The method used to estimate the movement in the deficits over the three-year periods presented below is necessarily simplistic. We expect scheme actuaries to have access to more detailed scheme data, which will allow a more in-depth reconciliation to take place. The method and simplifications we have made in these reconciliations are contained in the methods, principal assumptions and limitations section.

In Figures 5a and 5b, the starting deficit for all schemes has been notionally set to 100 to allow for easy comparison of the change over the period. The size of the bars shown on the chart illustrates the relative impact of each of those items on the deficit over the period. As deficits decrease and schemes move into surplus, we will review how we set the starting deficit.

Figure 5a: Estimated impact of market conditions on deficits of all Tranche 17 schemes – December 2018 to December 2021

Sources: TPR, Refinitiv

We estimate that there is a small aggregate surplus across Tranche 17 schemes as at 31 December 2021, although the funding level has only changed by a small percentage. This is because the large additional return on assets along with DRCs that have been paid have been greater than the offsetting effect of the increase in liabilities due to the changes in nominal yields and increase in expected inflation. The impact from hedging is shown in the additional return on assets item and not the change of basis: notional yields or change of basis: inflation items. For the purpose of this analysis, we have not attempted to quantify the potential impact of COVID-19 on schemes’ mortality experience or assumptions.

Figure 5b: Estimated impact of market conditions on deficits of all Tranche 17 schemes – March 2019 to March 2022

Sources: TPR, Refinitiv

We estimate that the funding position of Tranche 17 schemes as at 31 March 2022 would have improved from three years ago. This is mainly due to additional return on assets to 31 March 2022 together with DRCs paid, with financial conditions increasing the liabilities by a much lesser amount. For the purpose of this analysis, we have not attempted to quantify the potential impact of COVID-19 on schemes’ mortality experience or assumptions.

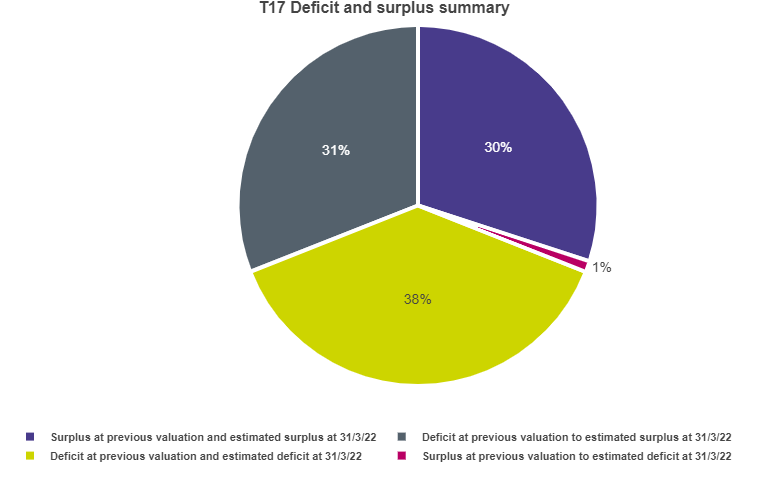

In Figure 6 below we have shown the proportion of Tranche 17 schemes which we expect to be in deficit or surplus on a TPs basis as at 31 March 2022 compared to the position at the previous valuation date.

Figure 6: Estimated number of Tranche 17 schemes in deficit / surplus at previous valuation and March 2022

Sources: TPR, Refinitiv

We estimate that 61% of schemes are in surplus on a TPs basis at 31 March 2022. The method and simplifications we have made in this analysis are contained in the methods, principal assumptions and limitations section.

Variation of impact on scheme deficits – all schemes

The analysis above will not be representative of the impact of market conditions on individual schemes. Different schemes will have had different experiences depending on their individual investment strategies and funding plans.

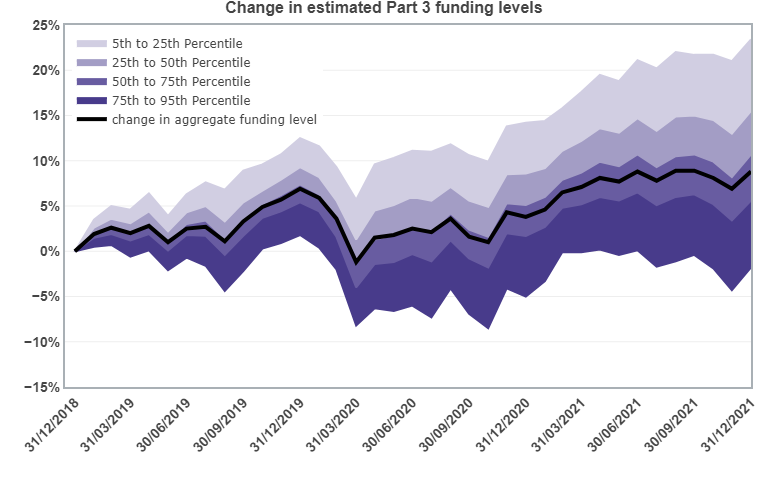

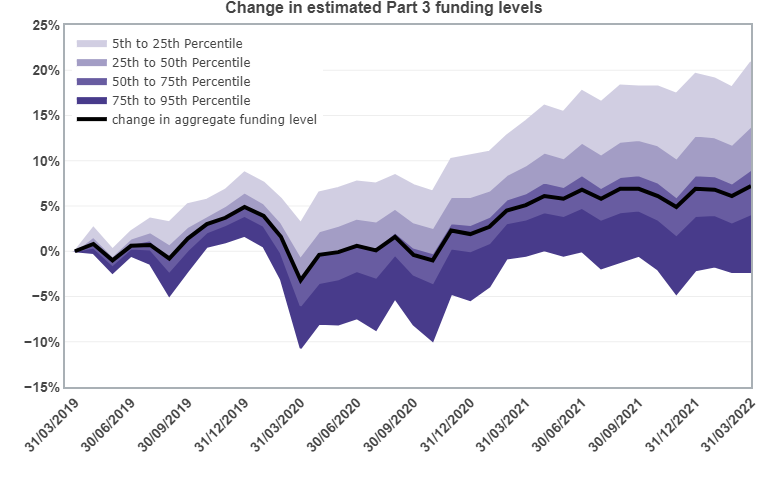

We have illustrated this variation in Figures 7a and 7b. These illustrations estimate how the funding level of each scheme has changed over the three-year period to 31 December 2021 (Figure 7a) and to 31 March 2022 (Figure 7b) for the whole universe of schemes (ie not just Tranche 17). Note that these illustrations show changes in funding level and not the funding levels themselves.

Figure 7a: Variation of impact of market conditions on deficits of all schemes – December 2018 to December 2021

Sources: TPR, Refinitiv

The average funding level at 31 December 2021 was higher compared to three years earlier (by around 9%), as has already been illustrated in the earlier analysis (for example Figures 4 and 5a). However, the experience of individual schemes varied significantly. Five per cent of schemes saw estimated funding levels fall by 2%, whereas 5% of schemes saw estimated funding levels rise by more than 23% over the three-year period.

Figure 7b: Variation of impact of market conditions on deficits of all schemes – March 2019 to March 2022

Sources: TPR, Refinitiv

Over the three-year period to 31 March 2021, the average funding level was higher compared to three years earlier (by around 7%), as has already been illustrated in the earlier analysis (for example Figures 4 and 5b). However, the experience of individual schemes has varied significantly, but for the vast majority of schemes was positive. Five per cent of schemes saw funding levels fall by more than 2%, whereas 5% of schemes saw funding levels rise by more than 20% over the three-year period.

The most significant factors in driving the variation of experience between schemes are the extent to which schemes hedge interest and inflation rates and the extent to which schemes are invested in growth asset classes (eg equity and property). At 31 December 2021 schemes that had hedged interest rate and inflation risks appeared to have slightly improved funding levels while unhedged schemes were behind targets. The position is less clear for schemes as at 31 March 2022 depending on their level of inflation hedging and inflation linkage in benefits. However, as noted in the AFS, hedging itself is not intended to provide outperformance, but is employed in effective risk management to reduce downside risks and volatility.

During the first quarter of 2022 most asset classes fell in value. This included falls in the value of bonds and gilts, and consequently the yield on gilts has risen (and to a lesser extent so have the inflation expectations of investors in the gilts market). Given the above, we expect aggregate funding levels as at 31 March 2022 to have increased proportionally less than those at 31 December 2021.

Employer trends

As well as the impact of market conditions on a scheme, changes in the strength of the employer covenant are a key consideration for trustees and employers when considering funding plans and integrated risk management.

In previous years’ analysis we have shown trends in potential employer affordability, which were based on historic publicly available information. Given the significant and uneven impact of the Russian and Ukrainian conflict, COVID-19 and Brexit on scheme employers, for many schemes recent historic trends in employer affordability are likely to be of limited use in assessing employer affordability today. Consequently, we have again excluded trends in employer affordability from this year’s analysis.

Implications for scheme funding

The analysis in this report shows that many schemes with valuations as at December 2021 and March 2022 will have a smaller deficit than those revealed at their previous valuation date or may be in surplus.

In practice, the Russian and Ukrainian conflict, COVID-19 and Brexit may have impacted the strength of the employers’ covenants, which should be reflected in the TPs. This has not been reflected in our analysis. Strengthening of TPs will increase the deficit and, if the RP end date is to be maintained, will lead to higher DRCs than our analysis shows.

The Russian and Ukrainian conflict, COVID-19 and Brexit will also have impacted the extent to which some employers can afford to make DRC payments. For some employers, affordability will have significantly reduced, at least in the short term.

Therefore, we recognise some trustees will need to make changes to their TPs and RPs to reflect changes in the strength of the employer covenant, the scheme’s funding level and changes in extent to which employers can afford to make DRC payments.

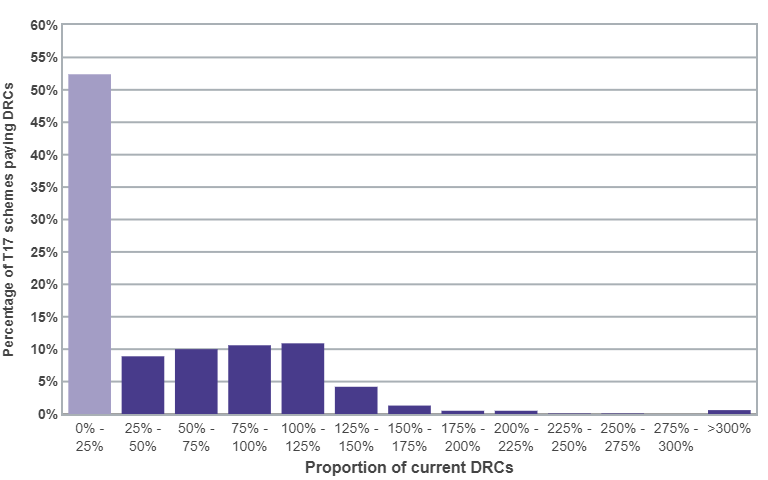

Potential impact on DRCs – scheme funding levels

Figure 8a below illustrates the potential impact on DRCs for Tranche 17 valuations assuming a 31 March 2022 valuation date. The impact is expressed as a percentage of the level of current DRCs (ie what was agreed in Tranche 14 valuations). We have assumed, for the purpose of illustration and to remove the distorting impact of short remaining periods, that each scheme aims to eliminate the deficit over three years, or the remaining term of the RP agreed at the last valuation, whichever is longer.

Figure 8a: Modelled Tranche 17 DRCs as a proportion of current DRCs – based on same RP end date as last valuation, or three years if longer

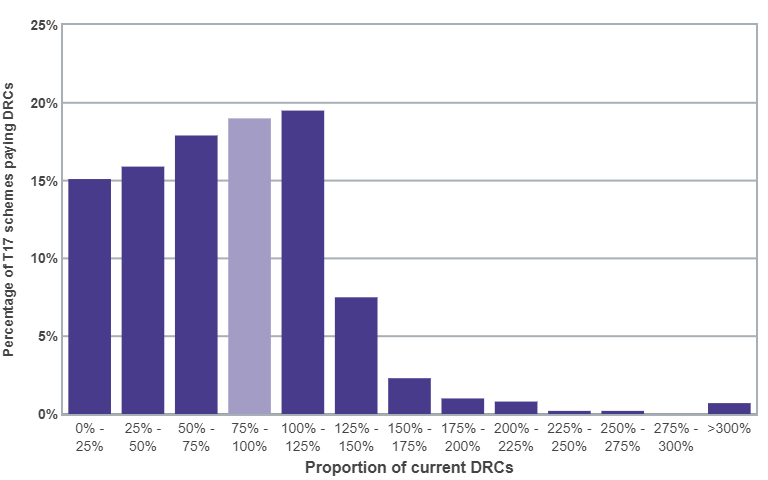

When a scheme moves from deficit into surplus, they are included in Figure 8a with a 0% proportion of current DRCs. As a lot of schemes have moved from a deficit position at the previous valuation to showing a surplus as at 31 March 2022 (see Figure 6), including them in the chart does not give a representative picture of the DRCs we expect to be paid for those schemes still in deficit. We have therefore removed them from Figure 8b below.

Figure 8b: Modelled Tranche 17 DRCs as a proportion of current DRCs – based on same RP end date as last valuation, or three years if longer (excludes schemes now expected to be in surplus)

On these assumptions around 68% of T17 schemes in deficit would be able to retain their DRCs at the same level or reduce them if their valuation date was 31 March 2022. Thirty-two per cent of schemes would need to increase DRCs. Around 1% would need to increase DRCs to more than three times their current levels. Some of this latter group of schemes would need to increase DRCs by a much higher factor than three.

Further examination of the schemes in the last category showed that many of them currently have shorter RPs than the average. In these cases, a relatively small increase in the RP length would lead to a much lower increase in the level of DRCs required.

This analysis does not take into account whether the TPs represent the current strength of the employer covenant, whether the current level of DRCs remain affordable, nor does it consider what level of contributions is affordable.

Potential impact on DRCs – employer affordability

A key factor for trustees and employers when agreeing an appropriate RP is the affordability position of the employer, recognising that what is affordable may be affected by the employers’ plans for sustainable growth. The Russian and Ukrainian conflict, COVID-19 and Brexit may have impacted the extent to which individual employers can afford to make DRC payments. For some employers, affordability will have been significantly reduced and will be the limiting factor for DRCs, at least in the short term.

Methods, principal assumptions and limitations

Scheme data

We rely solely on the information supplied to us via scheme returns, which may not be completely up-to-date or contain the level of detail that would be available to scheme actuaries when advising trustees. This inevitably leads to many more simplifications and approximations in the methods we use to estimate aggregate and individual funding positions, compared with the more robust calculations carried out for formal valuation and RP reporting by scheme trustees.

Many of these assumptions or simplifications have been driven by data limitations. For example, we have used index tracking of major asset classes, made no allowance for detailed changes in asset strategy since the previous valuation, and made only a broad allowance for the effect of hedging instruments to mitigate interest rate or inflation risk.

Additionally, we have made assumptions about scheme liabilities in aggregate that may not accurately reflect the underlying liabilities of individual schemes.

The baseline for estimating the current deficit of each scheme is based on the results reported to us following its last valuation, adjusted approximately for contributions paid and movements in assets and liabilities in line with appropriate indices. Our analysis relies upon point-in-time valuations of schemes’ assets and liabilities. We have not allowed for any changes to the TPs to reflect any change to the employers’ covenant since the last valuation.

As in previous years, we have seen evidence of schemes investing in more matching assets. We have also considered how discount rates may have changed as a result of changes in expected returns on return-seeking assets since the previous scheme valuation and have seen a variety of views. For the purposes of this analysis we have adopted a similar discount rate premium as at the previous valuation.

We have also made an allowance for the alignment of RPI to the CPIH from 2030. Based on the average maturity of the universe of schemes and the expectation that the current RPI curve factors in the change from 2030, we have assumed that the gap between RPI and CPIH will be 0.05% lower than at the previous valuation.

For the purposes of our aggregate analysis, to estimate the level of hedging, we use PV01 and IE01 data provided along with the scheme’s asset data. If these aren’t available, we make an assumption based on the scheme’s asset portfolio as to the extent of interest rate and inflation hedging.

When estimating the impacts on RPs, we have used the simplifying assumption that all Tranche 17 schemes have their next actuarial valuation as at 31 March 2022.

The assumptions we have made may be a significant source of difference when compared with formal valuation results at the individual scheme level. In particular, for individual schemes the results will be highly dependent on the following:

- the exact date of valuation

- the scheme’s asset strategy, including any changes made during the inter-valuation period

- the extent of hedging against interest rates and inflation

- any changes to its mortality and longevity assumptions to reflect new information and emerging experience

- the scheme’s assessment of the appropriate discount rate and inflation assumption used to measure its liabilities

For example, if trustees choose to use discount rates that are higher than we have assumed, then the estimated liabilities and deficits are likely to be lower than those modelled in this analysis, and vice versa.

Employer and contribution data

We rely solely on the information supplied to us via scheme returns to identify our employer population, which may not be up-to-date or contain the level of detail that would be available to covenant advisers when advising their clients. This inevitably leads to many more simplifications and approximations in the methods we use to estimate aggregate and individual covenant support.

The information on DRCs we collect covers DRCs expected in each year of the associated RP, with additional information as to the date the RP began and ends. DRCs are assumed to be paid continuously: 1/365th of DRCs in year one of the RP are assumed to be paid on every day of the year.

Employer covenant

The strength of the employer covenant is an important element in scheme funding and a key part of integrated risk management. We use a number of metrics relating to employers to determine covenant risk. However, we recognise that this is a highly complex area and that a one-size-fits-all approach to looking at employer covenant would miss the many complexities and nuances of individual employers. For these reasons, we combine the use of metrics with professional judgement when assessing covenant.

Assessing the covenant is about understanding the extent to which the employer can support the scheme, now and in the future, including the risks to this support being available when it is needed. The focus should be on the ability of the employer to make cash contributions to the scheme to achieve and maintain full funding over an appropriate period, including addressing downside risks.

The Russian and Ukrainian conflict, COVID-19 and Brexit have resulted in considerable uncertainty over some employers' covenant strength and their affordability to address deficits in schemes. However, the impact will be varied across the landscape and some businesses will recover more quickly than others.

Glossary

Deficit repair contributions (DRCs)

These are contributions made by employers to the scheme in order to address any deficit in the value of the assets compared to the technical provisions, typically in line with the Schedule of Contributions and the recovery plan. For the purpose of this analysis, we have assumed current contributions to be those in year four of the RP agreed at the Tranche 14 valuation, except for RPs which were shorter than four years where we have assumed that the contributions paid in the last full year of the plan have continued. Throughout this analysis we have used DRCs in the context of the value the scheme receives without making any allowance for any tax benefit the sponsoring employer may receive.

Integrated risk management (IRM)

IRM is a risk management approach that can help to identify, manage and monitor the factors that affect the prospects of meeting schemes’ funding objectives. It involves examining how employer covenant, investment and funding risks relate to and are affected by each other. It also considers what to do if risks materialise.

Recovery plan (RP)

Under Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004, where there is a funding shortfall at the effective date of the actuarial valuation, the trustees must prepare a plan to achieve full funding in relation to the TPs. The plan to address this shortfall is known as a recovery plan.

RP length

The RP length is the time that it is assumed it will take for a scheme to eliminate any shortfall at the effective date of the actuarial valuation, so that by the end of the RP it will be fully funded in relation to the technical provisions.

Technical provisions (TPs)

The funding measure used for the purposes of Part 3 valuations. The TPs are a calculation, undertaken by the actuary, of the assets needed at any particular time to make provision for benefits already accrued under the scheme, and required for the scheme to meet the statutory funding objective, using assumptions prudently chosen by the trustees. These include pensions in payment (including those payable to survivors of former members) and benefits accrued by other members and beneficiaries, which will become payable in the future.

Tranches

‘Tranche’ refers to the set of schemes that are required to carry out a funding valuation within a particular time period. Schemes whose valuation dates fall between 22 September 2021 and 21 September 2022 (both dates inclusive) are in Tranche 17. Because scheme-specific funding valuations are generally obtained every three years, these schemes (with a few exceptions) had their last formal valuation in Tranche 14 (valuation dates between 22 September 2018 and 21 September 2019).